On the use of the Historic Lectionary

Receiving a treasure preserved within Anglicanism

{Part of a series}

“Indeed, in all of catholicism in the twenty-first century, Anglicanism alone preserves the one-year Eucharistic lectionary that had been fully developed by the church by the seventh century.” - Gary Thorne

What is the Historic Lectionary?

It has been variously titled Classical Lectionary, Ancient Lectionary, One-Year Lectionary, &c., all of which are accurate titles. I expect I will use all of them in the course of this essay.

The history of the Ancient church both East and West has followed a general use of Epistle and Gospel for the readings for the Liturgy of the Word (or Liturgy of the Catechumen), the first half of the Eucharistic service, or Divine Liturgy. This lectionary, varying by jurisdiction, has been generally uniform in respective East and West use since around the 700s.

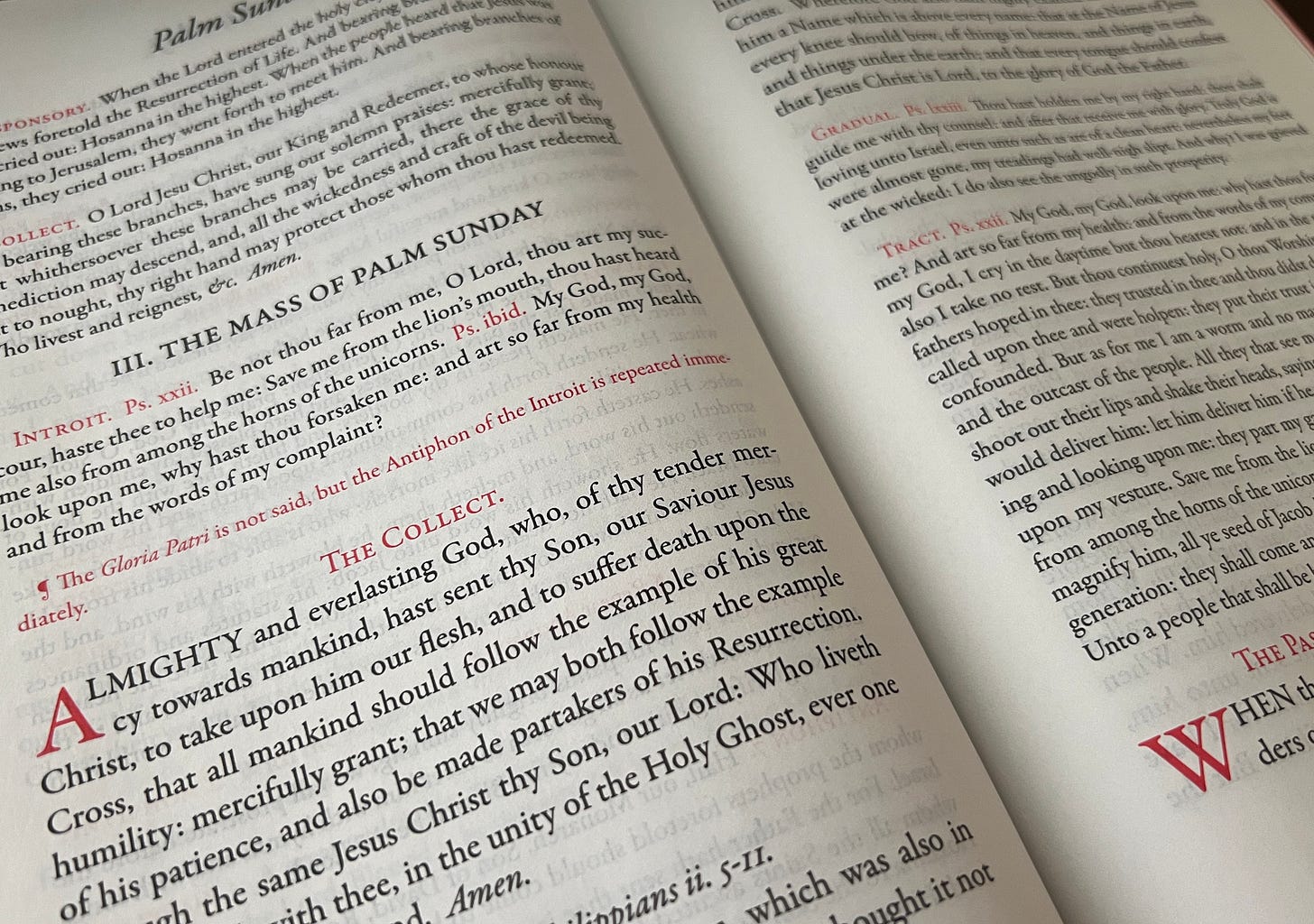

During the Reformation, the Reformers, specifically Cranmer, changed a few lections or tweaked a few prayers to illustrate the spirit of the age. Some classics, such as the Collect for the Second Sunday in Advent was new for the 1549 Book of Common Prayer:

Blessed Lord, who hast caused all holy Scriptures to be written for our learning: Grant that we may in such wise hear them, read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest them, that by patience and comfort of thy holy Word, we may embrace and ever hold fast the blessed hope of everlasting life, which thou hast given us in our Saviour Jesus Christ. Amen.

Yet, it retained the same readings (Romans 15:4-13 and Luke 21:25-33) and as the Roman & Sarum Missal of the day. In short, where Reformation seemed expedient, minor revisions were made to emphasize the principles held by those Protesting Rome. What was unreformed expressed a certain perspective of Catholic, patristic continuity valued by Cranmer, upheld by the Caroline Divines and later the bishops such as Bishop John Cosin, who negotiated the final form of the 1662.

Enter the 20th Century Revisions

The 1928 was a movement text: it was moving the liturgy forward in a direction, and the drafters of the revisions immediately set out to make for a further revised text, to take effect 50 years later. This period was a time of ecumenism as well as revolutionary scholarship. This was expressed through various movements: the Parish Communion Movement (It is good, actually, to take communion every Sunday), and the Liturgical Movement (Following Gergory Dix, let’s reassess our idea of Liturgy and structure of services). The fruit of this is seen most prominently in the results of Vatican II with the Novus Ordo service (with aesthetic revisions such as let’s think about minimalism vs maximalism), as well as a similarly revolutionary American 1979 Book of Common Prayer, which pushed the church outside of the English Catholic tradition and more into modern Ecumenical. Good things are in the book, but whether good or bad, it was seen as a revolutionary text, very observable in Marriage, Baptism, Confirmation, and Holy Communion liturgies. All of which expressed the theological trends of the 1960s and 1970s. For example, the (infamous) Eucharistic Prayer C:

At your command all things came to be: the vast expanse of interstellar space, galaxies, suns, the planets in their courses, and this fragile earth, our island home.

By your will they were created and have their being.

From the primal elements you brought forth the human race, and blessed us with memory, reason, and skill. You made us the rulers of creation. But we turned against you, and betrayed your trust; and we turned against one another.

Have mercy, Lord, for we are sinners in your sight.

Again and again, you called us to return. Through prophets and sages you revealed your righteous Law. And in the fullness of time you sent your only Son, born of a woman, to fulfill your Law, to open for us the way of freedom and peace.

By his blood, he reconciled us.

By his wounds, we are healed.

It is impossible to not see this prayer, and by association the editorial decisions, as expressing Theological Modernism of the 20th Century.

Along with these changes was a shift in culture and attendance, flagged by the various movements. People were not coming to church three times per Sunday, or even twice! The shift to industrialization meant that working hours took precedence, and church attendance began to be a Sunday Morning experience, with biblical literacy generally dropping as secularism increased through the natural processes of Modernism. At the same time, the Roman church was looking to bring about a reappraisal of Scripture in the life of the believer, as well as communicating in the vernacular—a key contention in the Reformation, but always practiced in the East. The Ancient Western Lectionary, venerable as it is, is not a comprehensive reading of Scripture. So the philosophy of liturgical revision was transferred to giving as much possible scripture to the people for the approximate hour or two they attended on Sunday. This is a good motive! As biblical literacy drops, it is good to expose people to more scripture.1

The historic lectionary followed a distinct pattern: the church year, with Trinitytide—the season from Trinity Sunday to Sunday Next Before Advent—focusing on the life of the church militant and discipleship of the believer. In short: the One-Year shows Jesus clearly, and what we are to do with his teachings, especially in relation to right preparation for the chief end of the liturgy itself: the sacrament of the Holy Eucharist. Epistle and Gospel lessons were tightly contextualized by the Collect for that week. The theme was unambiguous.

By contrast, the 3-year lectionary sought to roughly follow the church year, but instead of a focused, tight approach of Epistle, Gospel, Collect, generalized the approach with a priority toward greater exposure to scripture. Years A, B, and C would follow Matthew, Mark, and Luke, respectively; with John interspersed. Epistle readings would attempt to prioritize following whole books, Philippians, Ephesians, Galatians. This was designed without the Daily Office of Anglicanism in mind, for Roman use as it deprecated Latin as a service language.

So the two lectionaries have two different priorities;

One year: One particular narrative for one particular purpose, with the expectation of catechesis and reading in addition to the homilies and readings at the Holy Communion. While most of Church history has been on the one-year Ancient Lectionary, it is primarily2 the Anglican tradition (in the official BCP of most Anglican provinces: 1662; and in the St Louis Continuum in the 1928/Anglican Missal) still preserving this western tradition.

Three year: A more comprehensive, but broad, approach to the Gospels as well as Scripture, with the idea of introducing the Sunday-only attendees to as much scripture as possible through readings, with homilies more prominently walking through continuous readings. Most of the Western church, through Roman use is now on the 3-year Lectionary, or some derivative (Revised Common Lectionary, ACNA 2019 Lectionary).

One thing is clear: the Gospel is communicated whichever one uses, as it is Christ who is our Saviour and Sacrament, not the liturgy, lectionary, or another ‘formulae’ for relationship with God.

Arguments for the Historic Lectionary

At the beginning of Lent this year, with my bishop’s permission, I began trialing the Historic 1-year Lectionary. In the ACNA, there are a few cases that could be made for the right use of the Lectionary—all solid—and some arguably not needing Bishop’s permission, as its use is specifically upheld by the province (but I am not a canon lawyer and I asked my bishop; you should probably ask yours too!):

As the Standard: In an ACNA context, the 1662 is the standard for the Anglican tradition of worship,3 so no permission or limitation is needed, provided the standard is followed, which means that 1662 would be the expected prayer book alongside the lectionary. As the only specific edition enshrined in the Constitution, it is the least-limited book in the ACNA: some dioceses have banned (for a time) the 2019, and it is at the discretion of the province to deprecate the 2019 for a new revision.

As a sermon series: BCP2019, p. 718: “The Bishop of the Diocese is to be consulted where a regular pattern of fewer than four lessons is adopted as the Sunday customary of a Congregation, or when a pattern of alternate readings or a “sermon series” is proposed. The rector of a Congregation may direct that an appointed lesson be shortened or lengthened, provided the plain sense is retained.” This argument makes the case that the one-year lectionary is a sermon series, a repeatable, one year series. Supplementing with the OT Supplement of the PBS Canada also addresses the concern for many — clergy and lay — about having “only” two lessons at Holy Communion.

As conforming to prior use:

BCP2019 p. 7 “the ordering of Communion rites may be conformed to a historic Prayer Book ordering”;

BCP2019 p. 104 “The Anglican Standard Text may be conformed to its original content and ordering, as in the 1662 or subsequent books”

The 1979 was a revolutionary text, which, along with other mainline denominations, the Episcopal church participated in a great achievement of ecumenism: the Revised Common Lectionary. Rome, Lutherans, Presbyterians, Episcopalians, all began using a similar, new lectionary, alongside many adopting elements of the ICEL Eucharistic texts following Vatican II. But this was a wholesale, revolutionary changing of the Anglican tradition: not only were the rites aggressively modified, but the lectionary and collects were redone so as to dismiss the ancient provenance of the Anglican patrimony.

A communion rite is not complete without a Eucharistic Lectionary, so there is a solid case to be made that the Collects and Lessons are part of the Communion Rite itself. By conforming 2019 to the content of the prayer book(s) that preceded it, one aspect ignored is that one could conform the church year and readings to the Eucharistic cycle the church celebrated 1549-1978, the lessons and collects after 1549 only slightly differing from the Western use since about 700 .

Using a previously authorized book:

From the ACNA Constitution and Canons Title II, Canon II, Section 1,

“The Book of Common Prayer as set forth by the Church of England in 1662, together with the Ordinal attached to the same, are received as a standard for Anglican doctrine and discipline, and, with the Books which preceded it, as the standard for the Anglican tradition of worship. The Book of Common Prayer of the Province shall be the one adopted by the Anglican Church in North America. All authorized Books of Common Prayer of the originating jurisdictions shall be permitted for use in this Church.”

From the founding jurisdictions of the ACNA included the BCP editions of 1549, 1928, 2003REC, and Anglican Missal; as well the 1979 and Anglican Service Book. Some in considerable minority use (1662, Anglican Missal), but all of these, including Lectionary, are authorized in the province.

It is the entire use of some jurisdictions of the ACNA:

The normative Lectionary of the Reformed Episcopal Church, a self-running sub-jurisdiction of the ACNA founded in 1873, and the American One-year Lectionary remains its use. Given this, the One-Year is not an obsolete vestige, but one of current uses within the ACNA.

Unsurprisingly, I find the “1662 as standard” the most compelling argument in terms of permissibility, but as one who prefers 1928 and 1549 editions to the 1662, there are strong arguments using these as the basis of conforming the 2019 to these authorised Prayer Books where possible.

Old Testament Supplements

However, the ancient lectionaries include only two lessons: Epistle and Gospel. Many in contemporary parishes expect an Old Testament, and a Responsive Psalm (which is not the same function as the reading of Psalms in the Daily Office.)

There are a few options, one following strictly the 1928, 1662, or REC 2003, which is to supplement the First Lesson of the Sunday Morning Office to the Eucharistic Service. Samuel Bray, editor of the 1662:International Edition wrote a compelling case for this, which supports Keble’s Tract 13 , insofar as the Old Testament readings following their own, separate logic from the Holy Communion and a different cycle within the church year.

However, two challenges present when using these. First, many of the lessons are contrastingly long compared to the Eucharistic texts. This gives disproportionate weight to them during a service, where the length would be more expected in the Morning Office itself. Second, they are not matched to the readings, and it may be desirable to follow a synthesis of the old and new lectionaries: retain the historic Epistle/Gospel but integrate the RCL Track II approach by thematically connecting an OT passage to the lections, in order to support the homiletical focus within the lectionary.

In 2024 the Prayer Book Society Canada released a One-year Lectionary, which addresses both concerns. However, the use of these texts has no classical precedent, so counsel from one’s diocesan authority should be definitely be sought. Even though the case for the Collect, Epistle, and Gospel is strong, these are new, trial texts.

Permissible, but what about expedient?

There are many reasons for favoring the ancient pattern, but a good synopsis is most concisely covered in the introduction to the Prayer Book Society Canada’s One Year Lectionary Book, as well as more generally in a recent Prayer Book Society USA article by Gary Thorne on Prayer Book Catholicism.

The tipping point for me was living in “Ordinary Time” in the Revised Common Lectionary for many years: the lectio continua with what felt like generally mis-matched collects.4 It began to make preaching more of a drain — not because of the text but the incongruity and apparent ahistoricity of the philosophy behind the selection of the texts. It didn’t feel as natural for Holy Communion compared to the passages I read in the one-year lectionary.

A few years of consideration—study—has only increased my affinity for the more ancient lectionary, inasmuch as it seems of greater spiritual importance than a particular edition—or language—of a prayer book. It is part of the lifeblood of the Western Catholic spiritual tradition, which the English Church providentially preserved from ancient times, through the Reformation, and into the mid-20th century.

The fact that this was not reformed—when the eponymous 16th century revolution took hold—speaks to its universal (catholic) importance.5 It is not essential to the church, for globally the majority of the western church has moved to a 3-year lectionary; and in the East, a different one-year cycle is retained. And all use Holy Scripture to communicate the Gospel. So it isn’t all-or-nothing, but preservation of the spiritual treasures we have been given. In this way, Gary Thorne, writing in the Prayer Book Society USA’s magazine speaks to the universality of the Anglican use retained in the one-year lectionary:

“Indeed, in all of catholicism in the twenty-first century, Anglicanism alone preserves the one-year Eucharistic lectionary that had been fully developed by the church by the seventh century.” – from Robert Crouse and Prayer Book Catholicism

As parish priest, there are non-academic, pastoral reasons for supporting this alternate cycle, and without these, it risks a LARPy approach to tradition: if it is to be retained, it must have pastoral use within the mission and theology of the parish. My reasons are:

Catholic: as Chesterton says in Orthodoxy, “Tradition is the democracy of the dead. It means giving a vote to the most obscure of all classes: our ancestors.”

Just like the tradition of our classical prayer book, within the 1662's collects and lections is the ancient Western tradition; the 1662 in this respect offers worship and preaching of scripture within the continuity of all the saints and faithful who have come before us, Early, Medieval, Reformation, Anglo-Catholic.

As part of the Anglican Tradition, amid the many changes and revisionism in culture, a key missionary asset to outreach is a stable foundation upon which our church and worship is built: we have a firm foundation in history, not just rooted in the changes of the 20th and 21st centuries. I believe that the prayer book tradition provides a stable foundation-- a chain of custody going back to the 16th century, but with the lectionary back as far as the early church, where in some cases Luther may have preached on the same lection as St Augustine, as well Andrewes, Keble, Pusey. This rootedness is in-keeping with a core reason to follow in the apostolic faith: that our catholic worship, faith, and practice is familiar to Christians 500 years ago, as well 1000 years ago, that it might correspondingly be familiar to the same 500 years from now, if the Lord has not yet come. This is part of my belief in robust, hopeful Anglican identity being rooted in the maintenance and support of the classical prayer book tradition as much as the apostolic deposit of faith in the validity of our sacraments.

Confessions of a one year lectionary convert, Rev Mark Surburg (LCMS):

"The three-year lectionary has destroyed the coherence of the whole series of propers, making services thematically chaotic and the individual lessons, including the gospel, essentially immemorable. 'St Augustine and Luther wrote sermons on the same texts for the same Sunday, a marvellous sign of the invisible continuity of the Church over time and space, despite the cruelties of schisms. A Bach cantata, though composed for the Lutheran context, can usually be more or less directly transplanted to the Roman or Anglican context, and it still fits perfectly [because of the historic one-year lectionary].'"

On Changing Lectionaries (PBS Canada), Revd. Jonathan R. Turtle, Prayer Book Society Canada:

"I contend that the ancient lectionary of the Western church –dating back one thousand years if not more –better "shows" us Jesus in the Scriptures. To borrow an analogy from Irenaeus, it accomplishes this by arranging the readings in such a way as to display the face of our Lord. Or, to mix my metaphors and borrow from Origen, the key to opening the door to one room of Scripture is hidden in another room of Scripture. As such the traditional Eucharistic lectionary teaches us to read Scripture rightly by doing so in light of Scripture's true end, an encounter with the risen and living Jesus himself."

Theological: There is a time tested coherence to the collects and readings of the Epistle and Gospel, that the themes are tightly woven towards a particular end and sequence, the coherence of which is not shared in the 3-year Lectionary, one Sunday's collect which must roughly thematically match 12 readings (4 lessons x 3 years, if staying on RCL track 2 or ACNA). “Ordinary Time” (Trinitytide) seems to suffer most from this. But more importantly, the purpose of the 1 year lectionary is purported to prioritize Christian discipleship in relation to the church year, rather than broad scattershot approach towards scripture.

Fr Matthew Oliver, writing for the Living Church:

"The purpose of lectionaries, along with liturgies, creeds, and dogmatic statements, is among other things to provide for the church more concise articulations of "the fullness of saving doctrine" (to quote the Rev. David Curry's essay on the three-year lectionary). Thus, one has to ask whether more Bible in the liturgy has actually brought about a better knowledge of the Bible and, even more importantly, a better grasp of "the fullness of saving doctrine." – Why the RCL is killing churches

"The problem that the [3-year lectionary] faces is simply the impossibility of providing at the eucharist what can only be properly provided through the offices." – Why the RCL is killing churches

"The RCL sometimes proposes texts that are superficially "at odds" with each other, creating theological tensions that the preacher must then attempt to solve or leave unaddressed.' … 'Public recitation of these huge swathes of Scripture, all of which are basically unrelated to each other, can easily have a detrimental effect on nascent faith." – Why the RCL is killing churches, and what you can do about it

Educational

One year with the 1928 lectionary - The Living Church, D.N.Keane (PBS / TEC)

"With less text at each service to mark, learn, and inwardly digest, I found it far more likely that the sermon would touch on everything read and that I would walk out of the service remembering it. Less proved to be more.' … 'I also began to feel a more thematic unity across the Propers. This unity is something I often wanted but felt was lacking in the RCL." –

In Discipling children a problem with the three-year lectionary, Father Richard Peers, Church of England, writes that modern educational methods rely on repetition, which modern lectionary, taking three years to repeat does not provide; the one year repeats in parity with the cycle of the church year. Of the five options towards providing a repetition of scripture for the purpose of educating children, the fifth—that of reintroducing the historic one-year lectionary—is the most practical.

Save the Lectionary, Save the World, Andrew Sabisky

“Educational psychology is rarely mentioned in discussions of liturgy, perhaps for good reason. Yet the three-year lectionary and the modern form of the Mass contravenes some basic principles of the discipline. Cognitive load theory argues, on the basis of the empirically well-founded theory of working memory, that since we cannot simultaneously hold more than ten chunks of information in mind at once, teachers need to focus on direct instruction, repetition, and the committing of information to long-term memory, from whence it can be more easily recalled and manipulated. The modern Mass, with its proliferation of readings, stretches the cognitive capabilities even of the most intelligent congregation members beyond what they can bear.”

Homiletical.

Finally, provided these claims from other academics and pastors proves missionally and formationally fruitful for the parish as much as my own study, there develops a homiletical challenge, if used well would strengthen a preacher: maintaining repetition without monotony.

I have heard complaints at the year-to-year rut of some one-year lectionary preachers. But as I see it, I hope that I might become so familiar with the passages that my homiletical style can improve by way of leaving the manuscript and becoming more extemporaneous insofar as preaching for the people for that particular day and time. This is achievable in any repeated lectionary, but is more achievable when encountered every year versus once every three years.

The challenge, too, is that one must preach afresh having encountered a text repeatedly, and one must be sure to know well the gaps of the lections. There are gaps, and one must educate and walk through the biblical text in supplementary sermons and catechesis where the historic lectionary might lack a particular teaching. For example, the 1-year is light on the Bread of Life discourse, so the homiletical challenge is to bring that text in where the lectionary points to it but does not quote, as well as be willing to form theology outside of short Sunday homilies, both in bible study and catechesis.

Personal Reflections

My own experience on the lectionary has been inconsistent. I was formed primarily within a 1928 BCP context (Reformed Episcopal/former APA, and other continuing churches). So as a listener, I took in the historic lectionary early in my formation (when I cared little about lectionaries a all: the fact they existed at all was enough).

Yet while as a priest I was primarily formed in a 1928 BCP liturgical context, I was not exposed much to the one-year lectionary in practice; even the traditional prayer book churches often moved—or were moved—to the new lectionary. Some with the new collects, some inconsistently retaining the 1928.

My interest and study of the historic lectionary was initially out of historical interest: reading and researching on preaching in the Victorian era brought me to the texts that were read, then. Through this I have been intellectually persuaded of the usefulness of the one-year, even though it deviates from the majority practice in the West. Not just preservation for the sake of preservation, there is a solid case for its use—both in permissibility to adopt it, as well as the missionary/discipleship (Matthew 28:19-20) basis for doing so. After years of reflecting on the lectionary and its merits, I have decided to not just give it an intellectual treatment, but a practical trial.

So far engaging with the historic lectionary has been an incredibly freeing experience. Though only properly preaching for Lent6, I am already enjoying the well of wisdom of the saints having preached on many of these passages, as much as the tight connection of the lections with the collects. While I lost some go-to RCL resources I found quite helpful in homily preparation, the lections themselves have felt more appropriate and natural for a homily than my prior RCL Lent preaching. It feels as though these pericopes are designed to preach people towards Christ and in so doing, the Eucharist.

And as part of my trial, I have been supplementing the 1662 Eucharistic Lectionary with the Psalms (taken from 1662: International Edition), and Old Testament according to what the Prayer Book Society Canada developed. I chose to favor the 1662 lections vs 1928 because of the Fundamental Declarations of the ACNA (point 6), as above.

As I am in a diocese where this is not universal practice, and so connected with other churches and a godly bishop, which most prepare sermons on the ACNA or RCL cycle, I have made the following commitments in using this lectionary:

This is a trial, not an inflexible commitment; at that, one with reflection and analysis. If it is not working at the parish—bearing fruit in the way posited, argued for, and hoped for—pastoral responsibility requires that I examine why and adjust accordingly.

At any point where there is a visit or emergency necessity, whether episcopal visit or priestly supply, I remain strongly in support of following the RCL / ACNA lections for those occasions of expediency and convenience of the clergy visiting who are not familiar, etc. In that the Traditional Lections remain an option.

In fact, my chief complaint about the ACNA 2019 BCP is that it does not explicitly follow the 1662 it upholds to provide an option for the historic communion service. TLE would have been the ideal book to include two appendices: A) p.142 Service Order B) Historic Collects with table of one-year Eucharistic Readings. Thankfully, we still have the option, even if less accessible and whether in primary use at my parish, I am heartened at the new clergy moving towards the same tradition. It is part of the mission of Anglican.Center to continue supporting some of these lesser-resourced classical and catholic uses within a pan-Anglican context.

Of course, Anglicans have a robust tradition of the Daily Office Lectionary being a practical, comprehensive answer to the need for more scripture and thereby increasing biblical literacy. To follow that is to follow nearly the whole bible in 4 readings per day, with the Psalms over a year, harmonized with the Eucaristic readings.

As I recall, the Lutheran Church Missouri Synod has two tracks, being contemporary (3) or historic (1).

Fitting one collect with four readings: OT, Psalm, NT, Gospel, over three years. 12 readings for one Collect!

Again, the oft-cited Vincentian Canon

"We hold that which has been believed everywhere, always, and of all people: for that is truly and properly Catholic.” — St. Vincent of Lerins

I have for some time made it a habit to confer with the One-Year Lectionary and Collects as part of my preaching preparation for RCL homilies; when preparing I often said to myself “I wish I had that passage for this week.”